Writing Through the Dark Night

An interview with Carmen Acevedo Butcher from Blue Mountain Review

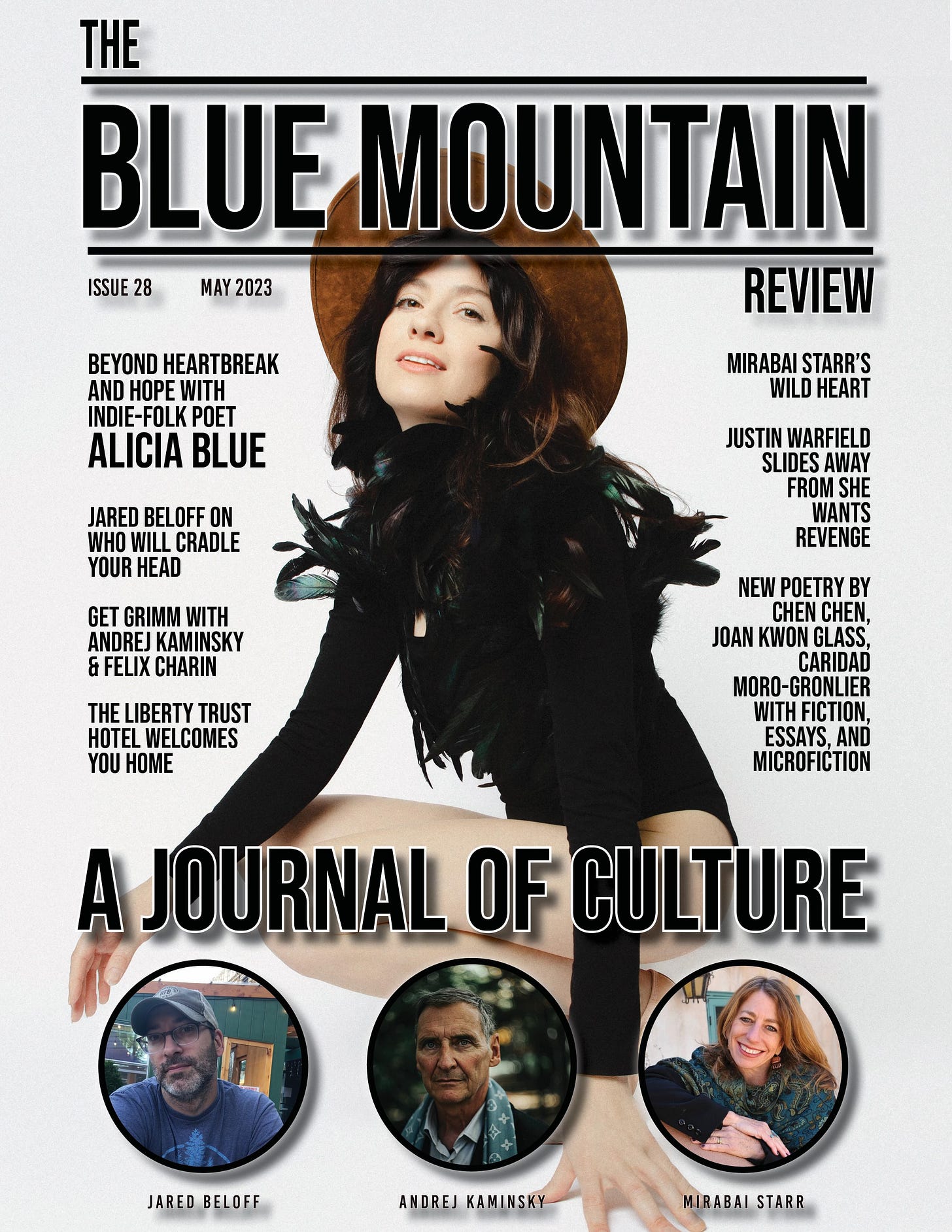

This week I’d like to share an interview with my dear friend and colleague, fellow translator Carmen Acevedo Butcher. This conversation was published in The Blue Mountain Review, a respected Southern-based literary and arts journal, part of The Southern Collective Experience, renowned for sharing a diversity of voices through poetry, prose, and visual arts, emphasizing genuine human experience. Some of it may feel redundant to readers familiar with my story, but for others it might be a handy overview.

Blue Mountain Review, May 2023. You can access the full issue of this magazine here.

1. Who is Mirabai Starr? What is it about your life that created you as a writer?

I grew up in the 1960s in a non-religious Jewish family that worshipped at the altar of literature. My parents were peace activists. The “lullabies” my mother sang us were protest songs. I thought every kid went to sleep to “Blowin’ in the Wind.” Recently, I sat with my 88-year-old mom and recorded as many of these songs as we could recall. It was both hilarious and deeply moving.

My parents were not only agnostic, but they actively disdained religiosity. They felt that religion was responsible for much of the suffering in the world, both historically and now. I was attracted to every single religion I encountered, which was embarrassing. While most kids were hiding that they smoked cigarettes or pot, drank beer and had sex, I felt like I had to hide my Buddhist meditation practice, my Sufi chanting and Hindu guru, my fiery desire for God.

But the seeds of activism were planted early, and they have flowered in my adult life. Action and contemplation have come together in me. And so have my literary voice and my spiritual path. I have no patience for preachy, pedantic spiritual books, for theology devoid of beauty. Last week my old Middle School teacher, Natalie Goldberg, who went on to become a well-known teacher of writing (with her best-selling Writing Down the Bones) sent me copies of the school literary journal we put out in the early seventies. I read a poem I wrote when I was twelve. Among all the psychedelic imagery was nestled line after line that showed my concern for people who are oppressed, my love of animals, my fears for the environment. That was 50 years ago! These are still essential themes in my writing.

2. You’re an acclaimed translator of Julian of Norwich, John of the Cross, and Teresa of Ávila, what drew you to each of them?

A lifetime of many losses has shaped me as both a writer and a translator. But the loss that catapulted me into a different universe was the death was my teenaged daughter Jenny. The only way I knew to survive this experience, to bear the unbearable, was to write my way through it. Naked and vulnerable writing, fierce and no-bullshit writing.

I’m still untangling and integrating the events of that day. Less than an hour after I received the first advance copy of my first book, a translation of Dark Night of the Soul by the sixteenth century Spanish mystic, John of the Cross, the police came to the door to tell me that they had found my daughter, who had been missing since the night before, and that she had died in a single-car crash. And so, the release into the world of my new version of this classic text on the transformational power of suffering coincided exactly with the deepest darkest night my soul could have imagined. Did it help? Not really. Nothing did.

But, throughout my first year of mourning my child, I translated Teresa of Avila’s mystical masterpiece, The Interior Castle, and it saved me. When I could not bear to do a load of laundry or return a phone call, I could go to my desk every day, light a candle, spread out my dictionaries, and translate a page. And then another page, and another.

The truth is, Teresa could be talking about anything—how to embroider a tea towel or the life cycle of the trout—and I would have found solace in her company.

After the Castle came out, I translated Teresa’s autobiography. Years later, after a few books about the mystics written in my own voice, I translated the medieval English anchoress, Julian of Norwich, who lived through wave after wave of the Plague and knew something about transforming sorrow into deeper compassion and greater aliveness.

What I love about translation is that it engages the whole of me: my love of language and my connection to spirit, the art of crafting a beautiful sentence combined with a sense that I am making these great wisdom figures accessible to a whole new audience who may or may not be religious. I try to bring up the universal notes in the texts, and frankly minimize the piety.

3. I’ve heard you speak of your next book, called Ordinary Mysticism. Do you want to give us a preview of it?

As I grow older, I find myself drifting father away from the mystics of the all the world’s religious traditions, who experienced exalted states of union with God, and toward the center of everyday life as the real dwelling place of the sacred. The subtitle of Ordinary Mysticism is “Your Life as Holy Ground.” I’m interested in helping people reclaim their ordinary experience as a portal to spirit, imbued with beauty and meaning, just as it is. I use many examples from my own life, and I also draw on the lives of ordinary-extraordinary people I know, from a Vietnamese nail technician to a Catholic priest who loves former gang members back into belonging.

4. How do we keep up with you online, and what projects and programs are on the horizon that we should be aware of?

I guide an online community called Wild Heart and have created a program called “Holy Lament” that explores grief as a spiritual path. There is an emphasis on writing our way into and through shattering loss. It feels like our culture is finally ready to turn toward grief rather than peddle endless ways to bypass this essential and transformational fact of the human condition.

Interview excerpted from Blue Mountain Review, May 2023.

These posts are free, but you are welcome to upgrade to a paid subscription if you would like to support my work.

Thank you for all your work. I had such an interesting peaceful time, visiting Avila, and setting in the little chapel near her bedroom. The other tourists were moving about in and out, but there was such peace there. I am recovering from the death of my son from Parkinson’s last year, and there in Teresa’s space there was a depth of peace.

I have such a similar experience of growing up mystically — and it led me to spend decades doing work as a spiritual activist. But this is a very different experience than many people — people I want to invite into this mystical movement. How do you suggest we best support the seeds sprouting in others?